A Lifelong Promise - The Story of Rev. Dr. Hsieh Wei【Parent-Child Reading Guide】

點閱次數:522

Hsieh Wei was born in 1916. In his hometown of Nantou, his father Hsieh Pin had founded a hospital called Tatung. His mother, Wu Shang-Jen, was one who took parenting and religious instillation seriously. When Hsieh Wei was 9, he miraculously survived a severe illness. While the Rev. Wu Tien-Ssu was praying for his recovery, Hsieh Pin and Wu Shang-Jen made the promise to God that Hsieh Wei be used in evangelical work. Curious enough, a teenage Hsieh did on his own receive that calling. Setting his sights on becoming a self-supporting preacher, he planned to enroll in seminary as a college graduate. It was not to be, though. For two years in a row he could not even pass the examination to enter high school. On his elders’ suggestion and encouragement, Hsieh went straight to Tainan Seminary instead. The Seminary gave him a solid foundation in the Christian faith, and cultivated him in philosophy, literature, sociology, and music.

Hsieh’s next step was to train in Japan to become a medical doctor. Toward the end of World War II, Hsieh had graduated from the Tokyo Medical School1 and been interning at a hospital in the Imperial capital. To evade Allied bombing, Hsieh asked for and was granted a transfer to Sendai, in northeast Japan. He did not, however, miss the air raids on Sendai in July and August, 1945. Warned by the siren, he escaped through the rear window of his dwelling, ran to a cemetery, and watched the house burn while catching breath atop a headstone. It was then that Hsieh realized that fear and running away were not the ways of a servant of God. He soon went back to Tokyo in spite of the danger.

Soon after the War, on November 17, 1945, Hsieh married Yang Chiung-Ying. Yang was also a physician studying in Japan, in addition to being a cousin of Hsieh’s. She fully understood and supported Hsieh’s vocation. Their wedding vows read,

May the Lord bless our Love,

So that thee I love more than this World.

I hereby offer myself

To thee only and forever.

The couple would transcribe these words by hand on every anniversary as an expression of their faithfulness and devotion to each other.

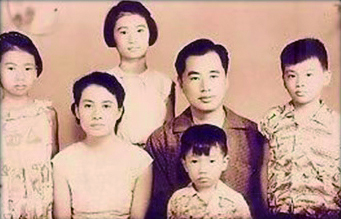

Hsieh Wei, Yang Chiung-Ying and their children. Photograph courtesy of Chen Chin-Hsing.

Hsieh returned to Taiwan in 1946. He served as a volunteer preacher in the local congregation and took over the running of Tatung Hospital from his older brother Hsieh Ching, who was of declined health. On Lillian Dickson’s invitation, Hsieh began providing healthcare for aboriginals. Throughout 1950 and 1951, he toured aboriginal settlements as a member of the Mennonite Church’s mountain medical corps.

In October 1951, Hsieh went to the United States for a three-year residency in general surgery. While he trained hard at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and at the Buffalo General, Yang reopened her practice to support the Hsieh clan. During the last year of the residency, Hsieh raised funds among his American friends in the hope of building a tuberculosis sanitarium for aboriginals in Taiwan. One of those who donated, Joyce Meredith McMillan, herself a medical-school dropout from Berkeley, was so touched by Hsieh that she moved to Taiwan in 1959 to work with him.

Back in Taiwan, Hsieh threw himself into the missionary partnership with Dickson, starting out in a bamboo shed in 1955. On January 16, 1956, the Christian Center-Clinic of the Mountains opened in Puli, Nantou County. A nursing school fostering aboriginal talent was attached to it in February 1958. The Clinic was the predecessor to the Puli Christian Hospital. Hsieh taught the nurses-to-be and took on most of the surgical work at the Hospital during its first ten years or so, until his resignation in 1970.

Lillian Dickson (first from left) and Hsieh Wei (second from right). Photograph courtesy of Taiwan Theological College and Seminary.

The tuberculosis sanitarium Hsieh fundraised for was set up in 1956 near Carp Lake (Li-yü T‘an), Puli. He built another for plains people in 1960, and traveled to Japan for several months in 1965 to learn a new kind of thoracic surgery. In the sanitarium, learning and participation on the part of the patients were promoted. The patients had, for instance, input to the menus, so they became more diet-aware at home. They could also grow vegetables and raise chickens on the premises, skills that translated well into the rest of their lives. After Hsieh’s death, his younger brother Hsieh Lun and Dr. Huang Chu-Hsin ran the nursing home for another ten years until Huang’s own passing. The Hsieh clan later handed over the land rights to the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, which transformed the place into a youth campsite in honor of Hsieh.

Dickson’s Mustard Seed Mission had a blackfoot-disease clinic in Peimen, Tainan County. Dr. Wang King-Ho was its director, but Hsieh was the surgeon in charge. Every Thursday, Hsieh took his team from Nantou to Peimen by taxi, the two-hour-and-some trip paid for with his own salary. He operated on the blackfoot patients and the poor folks in need of other surgeries for free, and often well into the night. Only then the team rode back to Nantou to start another workday. Hsieh labored thus for a decade before the government poured in any resources.

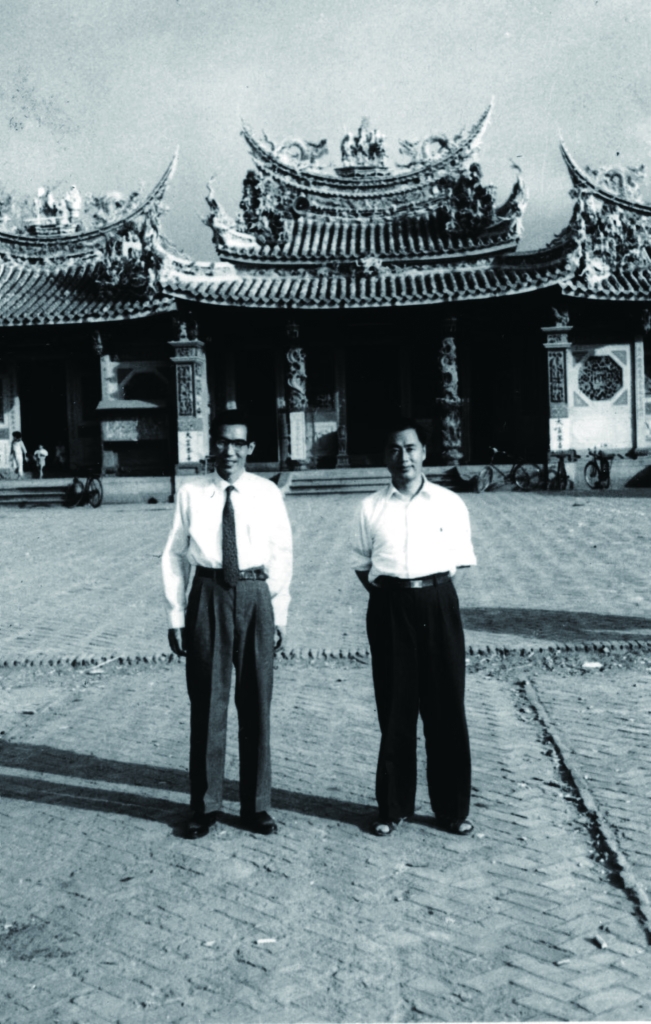

Wang King-Ho (left) and Hsieh Wei. Photograph courtesy of Taiwan Theological College and Seminary.

Toward the end of his life, Hsieh grew more and more concerned with the medical mission at coastal Erhlin, Changhua County. He almost never failed to commute between Nantou and Erhlin at least once a week. He was pushed ever forward by the idea that the Taiwanese should not depend on foreign aid forever. "The yam must take root," he once said to colleagues. "We ought to be mindful that it is time to do the work ourselves." On November 3, 1964, the Erhlin Christian Hospital, now a branch of the Changhua Christian Hospital, opened. Hsieh recruited from various healthcare institutions to assemble a staff that could best serve Erhlin’s population. The Hospital featured a poliomyelitis treatment center, where the aforementioned McMillan found her calling in caring for the disabled children. She settled in Erhlin, and later turned the center into the independent Joyce’s Home. Besides those hit with polio, Joyce’s Home has since 1980 also taken in children with developmental disabilities, and people of all ages suffering from cerebral palsy or dementia, including Alzheimer's.

Hsieh was killed in a car accident on June 17, 1970. He was on his way to Erhlin, having not rested after coming back to his home in Nantou from a morning shift in Puli. After lunch, Yang noted that Hsieh looked tired, but he insisted while dressing: "Every minute I arrive early, my patients suffer that much less."

Hsieh Wei lived his mere 55 years to the full. He was a medical pioneer who loved this land and the people who lived in it. He was a Taiwanese.

1 Known as Tokyo Medical College since 1946, and Tokyo Medical University since 1998.

* This reading guide is adapted from Dr. Lin Hsin-Nan's Review on Hsieh Wei and His Time. The review was published in Medicine Today, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 327-330, 2004.

* The author would like to thank Chen Chin-Hsing and Rev. Loo Khebeng for advising on the contents of this book, and Yang Chiung-Ying and Hsieh Hui-Hua (daughter of Hsieh Wei) for granting interviews and lending a helping hand.