The Missing Statue: The Story of Engineer Hatta Yoichi【Parent-Child Reading Guide】

點閱次數:492

Beliefs Make the Character

Hatta Yoichi (1886–1942) was born to a wealthy peasant family of today’s Kanazawa, Japan. Jodo Shinshu introduced him to the notion of equality among individuals regardless of status and class. Another of his early influences was Nishida Kitaro. As the ethics professor in Hatta’s higher school, Nishida made altruism a staple of his curriculum.

In 1907 Hatta entered Tokyo Imperial University’s Faculty of Engineering and was placed under the tutelage of mathematics and civil engineering professor Hiroi Isami, a Christian. “If you are to build a bridge, build one on which people can walk at ease,” Hiroi told his students. Hiroi also liked to quote Aoyama Akira, another established civil engineer, as saying, “My sole purpose in life is to contribute to humankind, and I shall strive for that until the day I die.” Armed with the same sense of duty, Hatta decided against staying in Japan upon graduation and moved to Taiwan to start working.

Erecting Water and Sanitary Works in Taiwan

There had long been malaria, cholera, and plague simmering in Taiwan. To forestall epidemics, the colonial government saw the need for water supply and sewage systems in major settlements. In 1914, Hatta took part in the Tainan Water-course project under his role model Hamano Yashiro as an engineer for the Government-General of Taiwan.

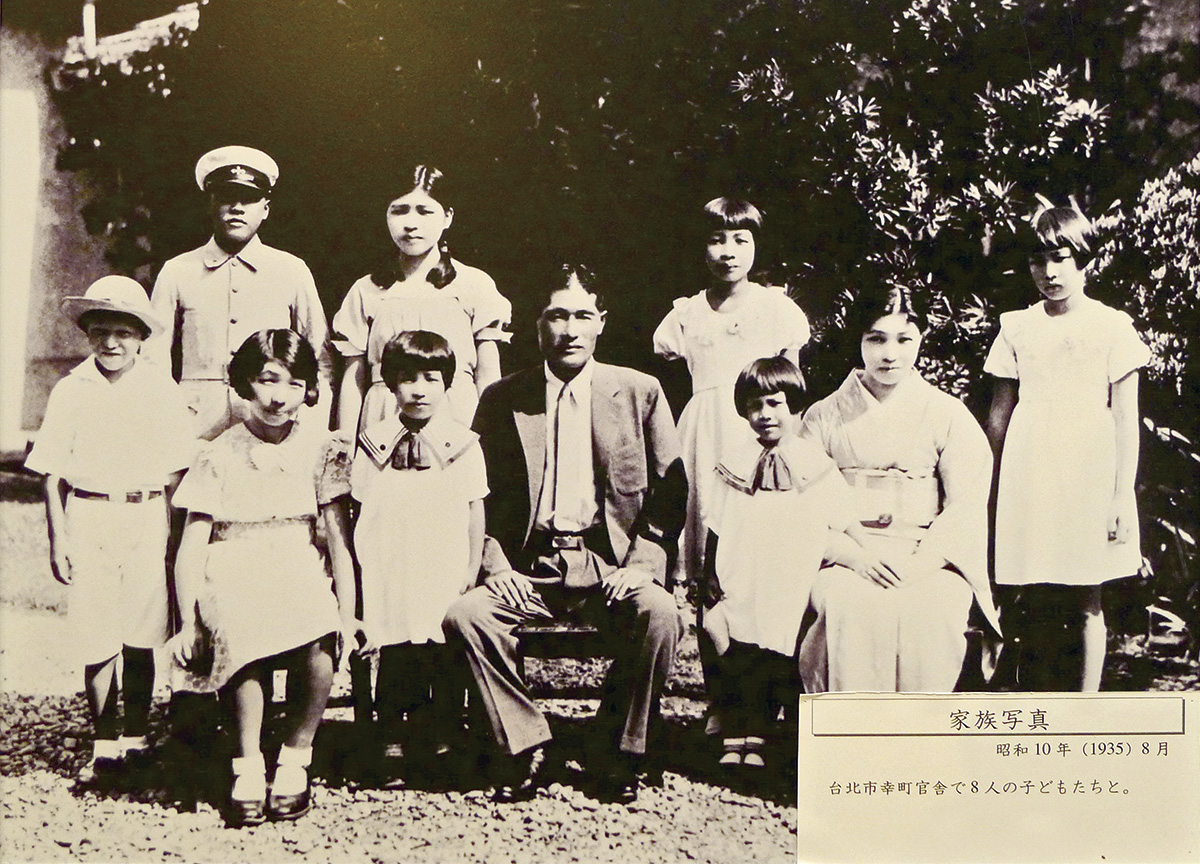

In August 1917, Hatta took leave from work to marry a woman, Yonemura Toyoki, in Kanazawa. Toyoki’s mother was somewhat against the match, for Hatta’s career was in underdeveloped Taiwan, but Toyoki seemed determined and content to follow Hatta to whatever hardship ahead. Indeed, the couple would spend their next decade in remote Wushantou. The Hattas had eight children together, six girls and two boys, all born in Taiwan.

Hatta Yoichi with his family (image reproduced by the author from a display at Great People of Kanazawa Memorial Museum)

Wushantou Reservoir and Chia-Nan Canals

Hatta surveyed the Chiayi-Tainan Plain in 1918. He found that the land was arid in fall and winter, but prone to flooding in spring and summer. Compounded with the high salinity of the plain’s coastal parts, it was of no surprise that the farmers in the area could barely make a living.

Hatta proposed building a reservoir at the upper reaches of Kuantien River. The embankment holding the reservoir would be the third-largest in the world and the largest in Asia at that time. The dam would be filled semi-hydraulically; that is, using a building method that was untested in Japan and all of Asia, the dam would be concrete only at its core, while most of it was made of rocks, gravel and clay. On the other hand, the canals bringing the irrigation water to the 145,500 hectares downstream would grow to be 16,000 kilometers in total length, or thirteen times the circumference of the island of Taiwan, or nearly half of Earth's circumference. Hatta projected that the water would wash away the salt in the soil and improve the harvests of the Chiayi-Tainan Plain. In September 1920, the union of the would-be beneficiaries of the dam and the canals began the construction.

Hatta, who had been on a business trip to the United States, brought back construction machinery including steam shovels and twelve German-made locomotives.

For the workers to focus on their tasks, Hatta designed home-like dormitories so that their families could live with them. The community was equipped with hospitals, schools, shops, and recreation facilities like kyudo ranges, swimming pools. To eradicate malaria in the community, Hatta and Toyoki also dispensed quinine door to door.

The Tunnel Through Wushanling

The reservoir required more than Kuantien River and precipitation to fill. To draw water from a larger tributary of Tsengwen River, a tunnel must be built through a watershed hill called Wushanling. The tunnel was completed in 1929 after several stoppages and re-designs, including one caused by a leaking gas deposit along the route whose explosion took more than fifty lives.

The Great Kanto Earthquake struck in September 1923. To fund the relief efforts, the Japanese government made cuts to various areas of its budget. The subsidy for building the canals was so impacted that half of the workers had to be let go, at least for the time being. Counterintuitively, Hatta kept the less productive ones, who might have a hard time surviving in the job market. He laid off his better-skilled employees and did find new posts for them. The subsidy resumed a year later, and Hatta fulfilled his promise of hiring everyone back.

The Wushantou Dam was completed a year after the tunnel through Wushanling. On May 15, 1930, all six great locks of the Chia-Nan canal system were opened for the first time, and clean water flowed in modulation to every corner of the Chiayi-Tainan Plain.

To be fair, at the time there was not enough water in Hatta’s reservoir to fully irrigate the plain all year round. As a supplementary measure, Hatta divided the tilled patches of land into three classes. For each given year, one class would grow paddy rice, another would grow sugarcane, and the other assorted grains. The classes rotated their crops annually, forming a three-year cycle. The irrigation water was finite yet distributed evenly. The farmers, who used to be at the mercy of the weather, could now count on their land to produce. Though the rotation scheme forced some to change their farming practices and was controversial with regard to water charges, the plain community as a whole ultimately benefitted from it.

Passing on the Know-How

Hatta always felt that there were not enough civil-engineering technicians for the development of Taiwan. He therefore founded a civil survey school in 1934. The school was instrumental in fostering local engineering talent. It moved and restructured several times over the decades, and now lives on as Jui-fang Industrial High School in northeastern New Taipei.

A Monument, a Statue, and the Spirit Within

At the dam and the canals’ completion, members of the union set up a monument bearing the names of the 134 workers and family members who died of accident during the construction. The names were engraved strictly in order of passing, regardless of their owners’ social ranks, and did not distinguish between Japanese and Taiwanese. The members also planned a bronze statue of Hatta in gratitude for his unprecedented contribution. Hatta reluctantly agreed on the condition that the statue portray his usual true self. The finished statue had him sitting in work clothes, cheap boots, and puttees, as if lost in thoughts on the bank of the reservoir.

Toward the end of the Second World War, the Japanese government began seizing privately owned metal to make weapons and to prolong the war. Hatta’s statue was hidden in a railway storehouse at Longtian and spared the fate of being melted down. The statue resurfaced by chance after the war, prompting the union to buy it back. In light of the Kuomintang government’s policy of removing Japanese symbols, union employees dared not display the statue and kept it in Hatta’s former residence. It did not return to its place by the reservoir until 1981, when the political climate became more forgiving, and the government granted a restoration at Wushantou Reservoir.

Hatta's Legacy Lives On

The curtains of the Pacific War were raised in late 1941. The Imperial Japanese Army, in need of more colonial resources, employed Hatta to assess the cotton fields’ irrigation in the Philippines. On his way there, the ship he boarded, Taiyo Maru, was torpedoed and sunk by an American submarine. More than eight hundred perished on May 8, 1942, with Hatta Yoichi among them.

Every eighth of May, the union holds a memorial service in Wushantou for Hatta, who graced Taiwan with his expertise and notion of the public good.