The Storm Petrel's Dance: The Story of Tsai Jui-Yueh 【Parent-Child Reading Guide】

點閱次數:654

Initiation into Modern Dance: From Taiwan to Japan

Tsai Jui-Yueh (1921–2005), lauded as the mother of Taiwanese modern dance, was born to a Christian family of Tainan in Japanese Taiwan. The family ran a three-story hotel downtown at the time.

Modern pedagogy had already been introduced to Taiwan when Tsai began school. Women were having more and more intellectual and bodily agency. A woman giving speeches, performing dance or music in public, or working in an office or factory, was no longer a sight unimaginable. Parallel to this trend was the rise of national consciousness at both the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan. In certain social strata and circles, people were willing to try new things, and to draw what was required to rebuild identities from their traditional cultures as well as ideas from the West.

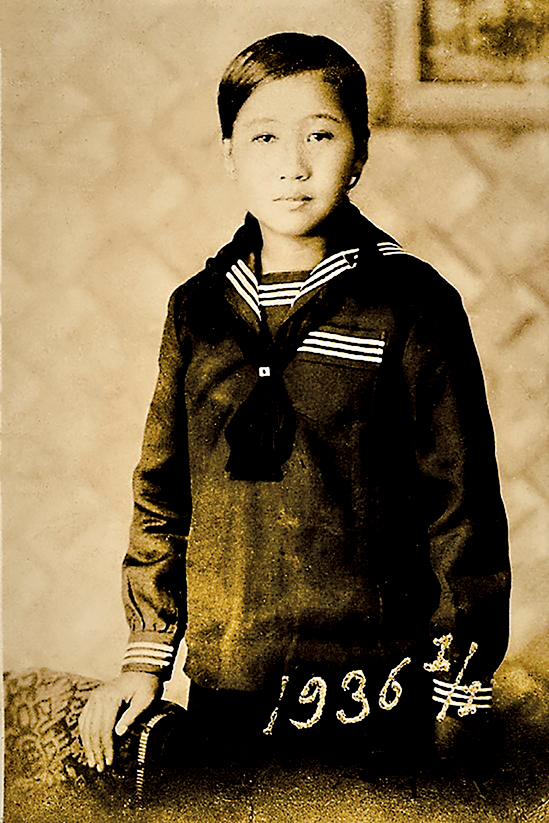

Against this backdrop, the Korean Choi Seung-Hee became a disciple of Ishii Baku, a Japanese modern dancer with classical ballet training, in 1926, and conquered the world in the 30s with her compositions expressing national characters and the will of the self. It is arguable that Choi’s Taiwan tour in 1936 set off the whole modern dance movement of the island. When Tsai was graduated from Tainan Second Girls’ High School, she went to Tokyo and enrolled in Ishii Baku’s institute and troupe. She later transferred to the school of Orita Hana, who was another student of Baku and who used the stage name Ishii Midori in honor of and as recognition from the older Ishii.

Tsai Jui-Yueh at Tainan Second Girls' High School (Photo provided by Tsai Jui-Yueh Dance Foundation, Taipei)

Back to Taiwan: A New Chapter of Modern Dance and Life

Despite Orita and friends’ imploring to stay, Tsai decided to return to Taiwan in 1946.

On board the Taikyu Maru, where she met many repatriating students as expectant and hopeful about Taiwan’s future as her, she composed and performed We Love Our Taiwan and The Song of India among other early works. She soon held her first recital at Thài-Pêng-Kéng Church, and opened her own

dance school in Tainan. She and her students made their Taipei debut in the former Taihoku Public Auditorium in 1947.

For about three years, Tsai reconnected with the land on which she was born and led the perfect life in terms of both career and love. Her husband was Lei Shih-Yu, a Chinese poet who came to Taiwan by himself in 1946 and managed to become a censor-curator for the Provincial Administration’s orchestra and a National Taiwan University associate professor. Lei took this petite young woman—modest and quiet at first glance but absolutely divine on stage—up and down various bureaucratic organs to obtain the permission and resources to perform. As for Tsai, she fell in love with Lei’s Tokyo-accented Japanese, and his scrupulous temperament that had evidently gone through a lot. As Tsai was about to leave southbound after a production in Taipei, both hesitated to part—at which moment Lei took off the antique watch on his wrist and proposed to her.

Their feelings for each other blossomed around the time of the February 28 incident. The union of two fully dedicated artists, one Taiwanese and one Extraprovincial, therefore worried Tsai’s family much. In any case, Tsai and Lei were wedded in a formal ceremony on May 20, 1947.

One of Lei’s poems for Tsai, If I were a storm petrel, was adapted into a dance about ten minutes long. The storm petrel in Maxim Gorky’s original imagery was the prophecy and call for a revolution as fierce as the tempest. However, in Lei’s diction and in Tsai’s moves and silhouettes, the storm petrel loved Taiwan, the island “the Sun embossed between Clouds ivory and Water celadon with Its versicolor Rays.” Despite the island being enveloped in the anxiety of “so many waves and storms”, the couple tried ever so hard to survive the political situation that was getting tenser each day and sheltered their toddler son, Lei Ta-Peng.

The Heart of a Dancer the Prison Gaols Not

The Kuomintang government put Lei under surveillance in 1949. In September of that year, Lei was deported and had to resettle in China. Lei’s communication with Tsai caused her to be moved around detention houses. She was interrogated for months in custody, and finally allowed to serve her baseless sentence on Green Island until early 1953. In prison, she led stretching sessions and composed simple pieces for her cellmates to practice as a way to relieve one another’s distress and dread. Heng O Flew Toward the Moon was also a product of Tsai’s time behind bars. Though it was an ensemble number commissioned by the warden, Tsai managed to imbue therein the sorrow of not being able to be at her father’s side during his final hours. After watching Heng O, a young political prisoner, Tsai Kun-Lin, who already planned to commit suicide regained his hope to live. He had been through the darkest sufferings for a whole year, but at that moment, he saw the dance from the heavens. In his exhilaration, he noticed the starlit firmament of that very night.

When Tsai was released, she was still trapped in a bigger corral. She had to tone down the free creative spirit she inherited from Ishii and Orita until her emigration to Australia in 1983. State-security agents harassed and interfered with her studio’s operation and performances almost daily, and caused her huge deficit. She lived in constant fear, especially of the authorities. In spite of all that, during the 50s and the 60s, Tsai left works that still resonate today: Death and the Maiden, The Puppet Goes to War (autobiographical); Bones of the Brave (anti-war); Tea-Picking Parade, Generals Tsiā and Huān, Song of the Rising Moon (locally themed); and the modern ballet play Graveyard Romance: A Story from Pu Sung-ling’s Strange Tales, which blended Chinese text, antique aesthetics, and electronic music into one piece. The Puppet Goes to War passed censorship and premièred in 1953. The work’s true meaning was uncovered by Tsai herself during its 2000 restoration: The characters are in fact the puppeteer and his marionette. The marionette, exaggeratedly rouged and lacking facial expressions in the beginning, seems to become freer, smoother, and more sentimental in her movements as the dance progresses, but at every turn it is revealed that the strings connected to her body are still in the puppeteer’s hands. Even as she finally takes the baby up from the cradle and holds it in her arms, the puppeteer retains control of the swing and the caress.

Faith and Other Support

The Christian faith was the main pillar of Tsai’s indefatigable mind, while dance was the manifestation of her hope for life. In her 1953 five-act modern-dance play on the Resurrection, Golgotha, she played Jesus Christ to vent her own burden and suffering. While she shouldered a symbolic cross in the dance, Tsai took solace in Jesus Christ who carried the literal cross.

The final and current address of Tsai’s dance school is a hiraya (Japanese one-story house) in an alley of Taipei’s Chungshan North Road. Like many historic buildings in Taiwan, the house was ‘self-combusted’ in 1999. While the site could be rebuilt, innumerable precious records and documents were forever lost in the fire. Tsai reconstructed from memory some of her numbers, 11 of which were performed in 2000 at New Stage.

The Storm Petrel at Rest

Tsai Jui-Yueh passed away in Australia in 2005. Her encounters in life were exact testaments to Taiwan’s long transition from political and social repression to democracy and freedom. She chronicled the history in her compositions of modern dance where Tsai transformed Lei’s symbolic meaning of a storm petrel from simple and innocent to steadfast and courageous. Since the 40s, Tsai fostered generations of dancers and knowledgeable audiences, who, due to her grassroots, proletarian teaching and performing methods, formed the basis only by which Taiwanese modern dance could have shined on the world stage later in the twentieth century.