This Is Our Hospital - The Story of Dr. Roland Peter Brown【Parent-Child Reading Guide】

點閱次數:444

Dr. Roland Peter Brown (1926–2019) was born in China, where his American father, Henry Jacob, evangelized while practicing as a qualified surgeon for forty years in places like Kaifeng, Honan Province.

Roland had two elder brothers who died young. Both of Roland’s parents were already in their forties when they had him. To escape from the Chinese warlords fighting each other, Maria Miller Brown, the mother, bade Henry goodbye and returned to the States for a time with their 9-month-old son in tow.

The Calling to Medical Mission

Roland completed primary schooling in China and was further educated in the US, China, and Pyongyang. It was not until 1941 that he entered high school and college in America. In his third semester as a medical student at the University of Chicago, something stirred in Roland that called him to be a missionary doctor. Sophie Schmidt (1924–2010), his fiancée, got the same quiver of the heart, and the two became long-lasting partners in everyday life and work.

The Korean War broke out in 1950. Roland’s draft notice came about two years in, enlisting him as a medic. The government, however, also respected the pacifist beliefs of the Mennonites, allowing Roland the option of alternative service. Through the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), Roland and Sophie were dispatched to Eastern Taiwan in 1953 as members of the Mennonite medical team on upland circuits.

Shortly following the couple’s arrival in Taiwan, a new act of the US Congress relieved Roland of all duty to the draft and the alternative service. He was discharged and could have set out for home on the spot, but he fulfilled his promise to the MCC and stayed to practice medicine in Taiwan for four whole decades.

The Adapting General Practitioner

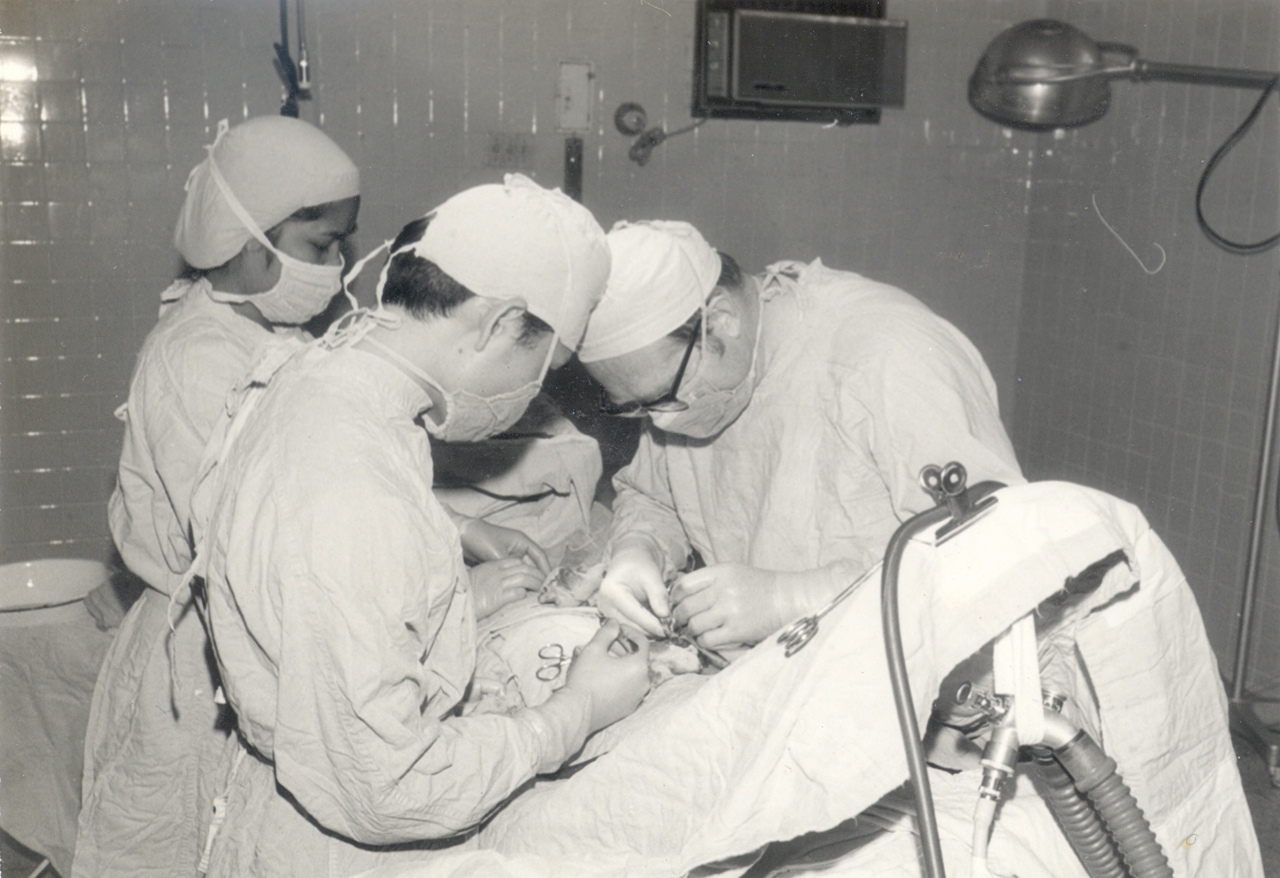

The initial challenges the Browns came upon when they settled in Hualien were the scarcity of medical supplies, equipment, and professional personnel for every task from giving intravenous drip, transfusing blood, to administering anesthetics. Roland had no one to help him with pathological diagnosis, either. Though a surgeon by training, he became a general practitioner in Taiwan. Between October 1953 and January 1955, when the Mennonite Christian Hospital (MCH) opened, Roland completed 87 major and 171 minor operations that spanned the fields of gynecology, orthopedics, gastroenterology, urology, plastic surgery, head and neck, and so on. There was just one life that he failed to save. Roland also treated parasite infections and tuberculosis, both of which were common among the aborigines. Furthermore, he produced the first-phase architectural plan for the MCH, relying on the elementary skills in technical drawing he acquired in college.

Roland took his time during operations in the pursuit of perfection. The stitching of cuts or wounds was given special care. The fundamental reason for such a modus operandi was the worth Roland saw in every patient’s life. He refrained from wearing masks when talking with consumptive patients. Regardless of how busy or exhausted he was, he always showed up before patients in clean and well-pressed clothes as a matter of respect.

Ahead of each operation, Roland led his team in praying for the patient and for God’s assistance. That’s not to mention the post-surgical recovery, which would be entirely God’s work. Though entitled to go home for rest after the operation, Roland invariably chose to have a quick meal at home and rush back to the hospital to monitor the patient’s condition, sometimes even staying by the bedside for the whole night. On the eve of a breast cancer patient’s surgery, Roland found that the woman was a widow raising an underage daughter. As she would be unavailable while hospitalized, the Browns took the girl in, thus settling the mother for treatment.

Dr. Brown, Warm and Thorough

Roland kept a notepad in his shirt pocket at all times. In it he updated his schedule as soon as an appointment was made, and he never failed to arrive at the place agreed upon on time. He did not talk much; everything he said was straight and to the point. Nevertheless, when it’s about human beings, he spoke in a soft and patient manner, with a natural smile to add to the words.

As a junior or student surgeon underwent training for a procedure, his or her senior colleague would usually demonstrate that procedure once. When the next similar case came along, it was up to the student to complete the procedure, while the senior would watch on the sidelines in a guiding role. Roland, in contrast, wanted his student to fully grasp what he was doing. After demonstrating the procedure, Roland would let the student take charge of a small segment of it and would give the junior colleague more responsibility in the similar cases that followed only if he or she had met Roland’s criterion for proficiency in previous segments. The student would not be asked to perform an entire operation until Roland felt that he or she had practiced and was confident enough. Roland’s method was more time-consuming, but he deemed it necessary to bring about soundly trained surgeons and answer to the patients.

In the course of surgery, the first mistakes of a nurse or student were forbearingly corrected by Roland. If a mistake of the same kind was made again, it would be met with stern criticism. Outside of work, though, Roland took good care of his employees. On holidays, they were invited to his home as guests for chat. According to the hospital rules then, a doctor had to fill out the charts of all cases in hand at the end of a month to receive the paycheck for that month. The resident doctors, however, were required to back up the emergency room, observe surgical procedures, make rounds, and work the night shifts at the wards. In other words, they were too occupied to finish the charts before a new month began. Without telling anyone, Roland would go into the room holding the clinical records and fill them all up, so that everyone got paid on time.

Sophie, the Partner in Service

Sophie co-administered the hospital with Roland. She turned over the job to a Taiwanese staff only after its operations were on track. She helped the women at the Halfway House for Unmarried Mothers, Hualien, regain their health and esteem, and cared for the disabled children at the New Dawn Institution. As her three children grew up and left the house, Sophie went back to the States to study special education in order to be of more concrete aid to New Dawn. The establishment of the kindergarten and English-language primary school of the Mennonite church in Meilun, that gave the missionaries a place to send their children to, was in part thanks to her.

Bearing Witness to the Lord’s Justice and Mercy

Roland was never on the Taiwan MCH’s payroll. His only meager stipend was from the American Mennonites as a missionary posted overseas. In the days of one NTD registration fees when the MCH first opened, there were still many who could not afford even that, let alone the expenses for surgery or hospitalization. For these patients, Roland would simply write ‘on me’ on their bills.

Roland came to Hualien, Taiwan, in 1953 when he was 27 years old to practice medicine. He retired in 1994 at 68. Forty years of underpaid missionary work did not afford the Browns comfortable later years, so their students and friends in Taiwan pitched in and bought them retirement housing in America. In retirement, Roland and Sophie never interfered with the running of the MCH. Instead, they prayed for the hospital and its staff daily. Those who worked there often got letters and cards from them full of words of encouragement and regard.

Sophie passed away in 2010, and Roland returned to his mansion in Heaven in 2019. He felt his 93 years on Earth were to live up to Matthew 25:40; that is, “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” And it was ‘service in the name of Christ’. It was Dr. Roland Peter Brown’s motto as a surgeon. It was what he did all life. It is what the Mennonite Christian Hospital is about, for those are the words carved on the institution’s foundation stone.

Awarded the Order of Brilliant Star with Violet Grand Cordon by President Lee Teng-Hui.

The present reading guide was adapted from Chou Tiang-Hong's articles Does Taiwan still need a medical missionary like Dr. Roland Brown? and Dr. Roland Brown: A good and faithful servant of Christ for the people of Hualien. For verification of facts, the author consulted Brown's memoir Healing Hands and Tall Mountains, Long Waters: Henry Jacob Brown and Roland Peter Brown in the East by Katherine Wu, both published by the Mennonite Christian Hospital.